The baths above the river in Tbilisi were hunkered down for winter: small, low domes over underground grottoes of sulfurous springs, vaulted chambers, womb-like, and the sound of dripping and bare feet. I remember, all these years later, that you could buy a forty of beer to take with you into the steam. I remember the woman who scrubbed us until we were babies again, and the tiles on the ceiling, the safe, revivifying feeling of easing cold fingers and toes into a warm bath. And the feeling that, as we came back to street level, back into the stark air, we had bundled up the warm feeling and could take it wherever we went.

This is the only way I can explain what it was to walk into Mtskheta Cafe a few months back, that feeling of thaw. We were dropped off by a Georgian Uber driver who told us casually, as we exited the car, that it was one of his favorite restaurants, one of the best in Brooklyn. It was pouring in Gravesend, and winter—I had just taken a train for an hour just to wait in a very long line on a very windy street for a very long time, rain whipping and umbrella inside-out, before giving up in search of lunch. Down there, you can hear the ocean, and an ocean in winter is one of the coldest things I can imagine, and to be wet and thinking about that is an uncomfortable thing.

I remember the descent on that first trip to Georgia, 2014—the rim of grey, foreboding peaks, how close the plane seemed to get to the snowy tops of them before suddenly we were in a wide, open bowl ringed by mountains in winter. Winter in the Caucasus is not like other places, someone told us, certainly not like where you came from. Winter is survival time, at least it used to be—big furs, tall boots—food for putting fat on you—cows in the barn, cheese in the cave—the wine is just-bottled—fires, feasts, wool. That Georgian winter fed me well, in small restaurants with clay ovens in the back room and in farmhouses with pitchers of backyard wine. Right after the baths I ate khinkali, my first ever, in awe that something so thick, so juicy, had ever existed, and yet I had been alive without it.

At Mtskheta Cafe the khinkali were nearly as good as my memory of those, the dough gummy like a boiled pig’s ear: something you sink your teeth into until it bursts into broth, porky and herby in its little purse. I asked for tkemali on the side, I like the tart astringency of those sour plums, and the waiter shook his head, saying nobody would really do that. Sour cream and adjika, thick red pepper sauce in a silver tureen, arrived swiftly, the request for tkemali forgotten. We also tried to order a glass of wine—not possible, bottles only. A bottle of Manavi, made with Mtsvane Kakhuri grapes. Georgians call it green wine, which makes sense when you taste it. At Mtskheta Cafe, listen to the waiter.

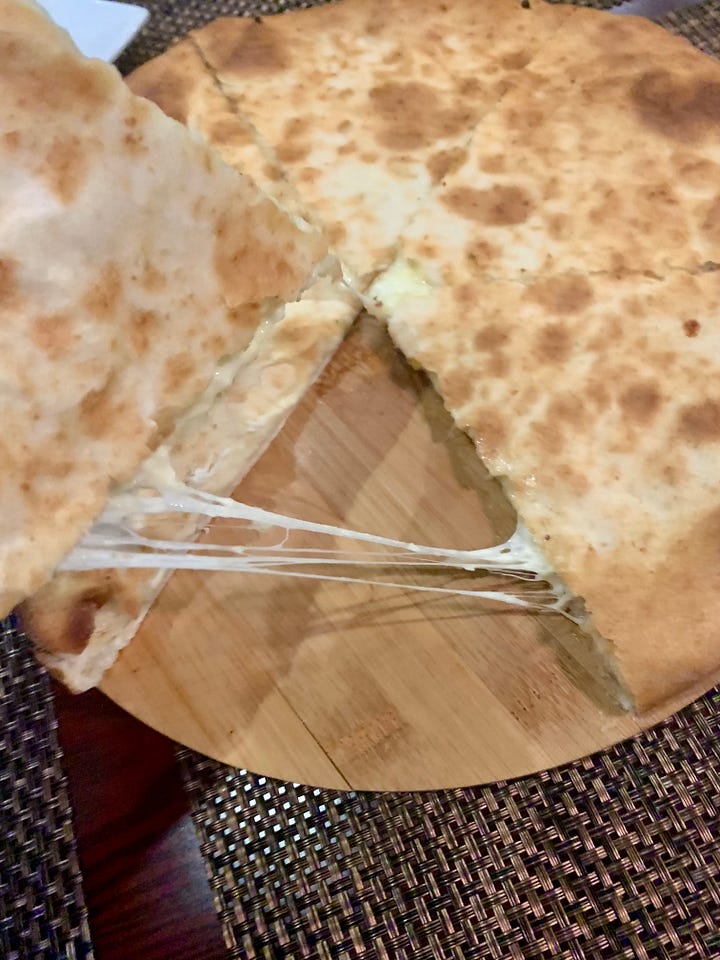

We also ordered Imeruli khachapuri, the round, enclosed version that’s cut into wedges from which ooze strings of tart cheese as you pull them to your plate or mouth. This isn’t the boat-style khachapuri—that one is from Adjara, where I once ate salmon roe on a stony Black Sea beach as an electronic music festival pounded in the far distance. Imeruli khachapuri is made with Imeruli cheese, melty but sturdy, feral, briny, squeaky, meant to be eaten with fresh spears of bread or bunches of bitter green herbs. Or to be folded into khachapuri, eaten with a slab of pickled red cabbage dyed an enviable magenta—soft crunch, tart and yeasty. Pickled cucumbers fanned out and tomatoes cut open like blooming tulips.

A cow grazing 10,000 feet above sea level, a clay oven blazing as a blizzard whites-out the landscape. Bread, cheese, cabbage; flour, water, scrapings of meat. And in the summer, when the grapevines are yellow-green and the mountains are full of hikers and bathers, the tart cheese is laid out with bunches of spring onions, sorrel and parsley, and long, pink, radishes, and the chicken is roasted over the coals, table heaving with salads. There are more “elegant” Georgian foods, you could say: thin, oily planks of eggplant wrapped in neat rolls around walnut paste and pomegranate seeds, consommé with lamb, sour plums, and piles of watercress and fresh tarragon. But my favorite Georgian foods rumble somewhere closer to the center, more at the heart of things.

Mtskheta Cafe is named for Mtskheta, a city old even for Georgia, one of the oldest in the world. When I visited, we walked around the freezing old town and the huge cathedral of crumbly frescoes and small dark sepulchers, an ancient complex surrounded by high crenellated walls. Before returning to Tbilisi, we drove up to Jvari Monastery: a lone church at the top of a tall, frostbitten mountain. We entered quietly, scarves over our heads. It was silent, only thin dripping candles and gold-framed icons, flat faces of saints with heavy eyes and many-folded garments of red and blue. Some were covered in glass for protection from the kisses, soft touches, and palms laid flat in prayer as eyes were cast upward. A low chanting began from somewhere—a recording, probably, though my mind conjured a priest hidden in one of the dark alcoves. For 1400 years the church has stood on the top of the rock, thousands of feet above town, looking out over the snake of the rivers and the snow-flecked brown and gold of hibernating trees. It has survived fires and wars, the sanding of the harsh wind. And still people come to Mtskheta to commune with their maker and come in from the cold.

would order again: assorted pickles, Imeruli khachapuri, khinkali, wine (any)

2568 86th Street, Brooklyn • (718) 676-1868