In Serbian, кафана means “tavern.” Or maybe something like “bistro,” but scuzzier. If Wikipedia is to be believed, a stereotypical kafana in the nations of former Yugoslavia is “a place where sad lovers cure their sorrows in alcohol and music, gamblers squander entire fortunes, husbands run away from mean wives while shady businessmen, corrupt local politicians and petty criminals do business.” A place, writes one of Wikipedia’s more dramatic editors, of “decay, sloth, pain, backwardness and sorrow.” In other words, the kind of place that I know in my heart will serve very good food.

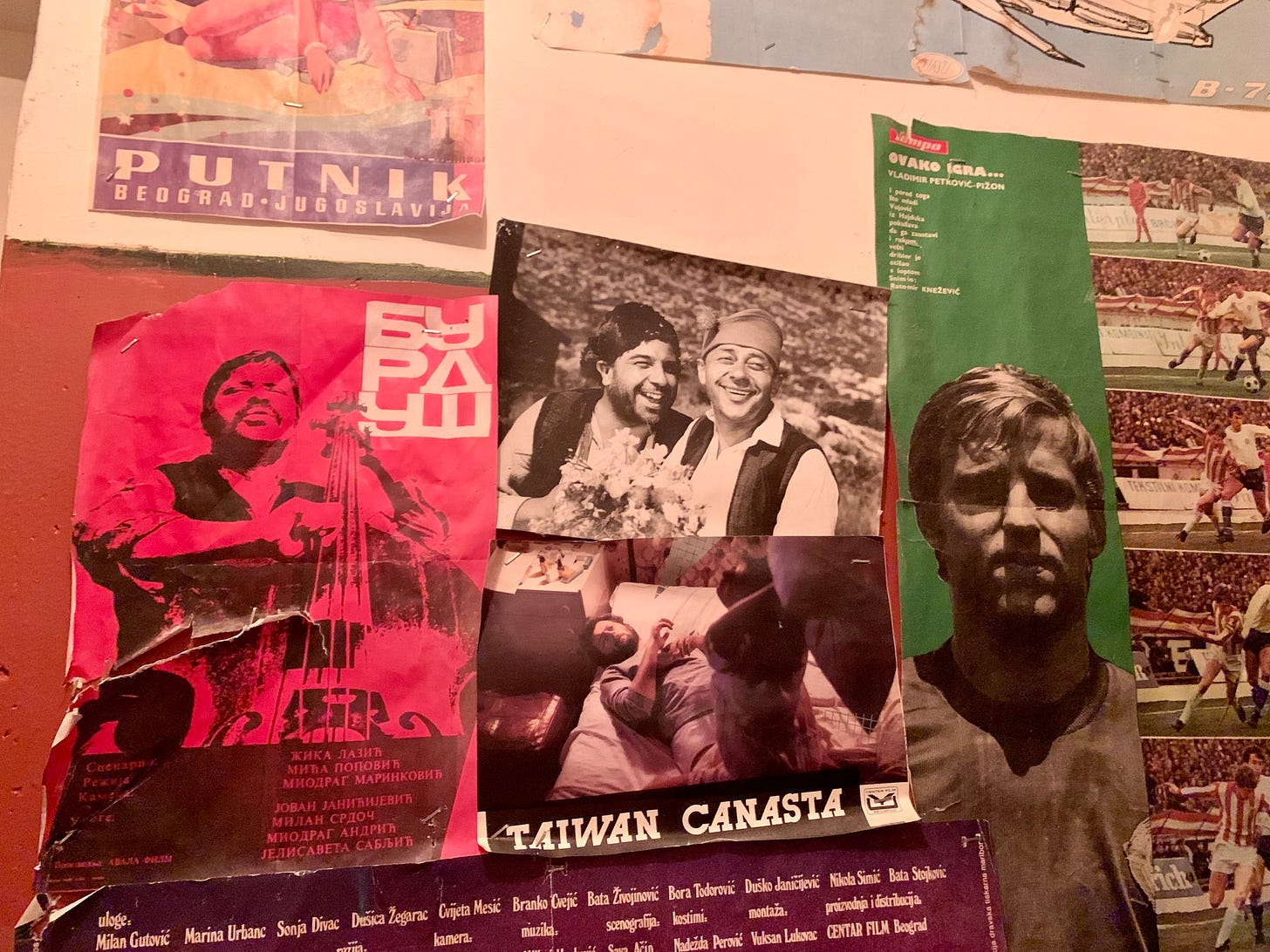

Kafana, the restaurant, is hardly a place of decay, sloth, pain, backwardness, or sorrow; it is a warm, cash-only restaurant in Alphabet City where the air is lightly perfumed with evergreen, porky smoke, and cigarettes. But it has that specifically sexy noir of the kafana of the mind and is filled, as I imagine any kafana would be, with a lot of people speaking Serbian and looking comfortably full. There are brick walls hung with crookedly framed babushkas and various fraternal organizations gathered around tables. In the bathroom, a vitrine holding pastel-plastic vials of Yugoslavian bath products; posters of smiling men in vests and scarf-wrapped heads, serious blond soccer players in uniform. Rows of bottles sit in little alcoves high above the tables.

Around the dining room, items of Orthodox ephemera are hidden in nooks that you spot when you least expect it, when you are looking around during a lull in the conversation. Like the shrine above the door to the kitchen; the icon looks like Moses with his tablets. Before him is a swinging censer that hangs from a bar jutting out of the wall. When I saw him, it was winter, and at his feet there were branches of juniper. And below Moses there was a large tin sign, a message in Cyrillic letters that I typed carefully into Google Translate: “The lottery drawing is tomorrow.” Moses gazes down approvingly. Many things can be true at once.

Something I think about a lot is The Language of Food, a 2014 book by the Stanford linguist Dan Jurafsky. It’s fast and fun to read—despite the many rabbit holes Jurafsky cannot help but go down—and packed with examples of how food culture is everywhere in the way we talk, and of how quickly food culture can change. Why is raising our glass to someone called a “toast”? Until just a few centuries ago, it was common in England to put a slice of sugared toast in your drink for flavor. “Bread itself was so central to the medieval English diet,” Jurafsky adds, “that the word for the Anglo-Saxon ruler in his great mead hall was hlaf-weard (loaf-keeper),” the ancestor of the modern word “lord.” The word “lady” is also Anglo-Saxon in origin, descended from hlaf-dige, which means “loaf-kneader.” (I would rather be a loaf eater??? But I digress.)

There’s a lot more where that came from, if you dig that kind of thing. (I feel like you do?) But what I think about so much is how Jurafsky’s book explores not only the language around food, but also the idea of food as language—with loans and semantic shifts and backformations and branching trees. “The language of food helps us understand the interconnectedness of civilizations,” Jurafsky writes, “… all brought together by the most basic human pursuit: finding something good to eat.”

The example that sticks with me is kind of a famous one: the constellation of dishes that orbit a common ancestor called sikbāj, “a sweet-and-sour stew with vinegar and onions loved by the Shahs of sixth-century Persia.” A history is reflected in the words for various vinegary fish dishes along the trade routes of the Mediterranean and beyond: aspic, escabeche, ceviche. And the culinary influence of sikbāj is clear in English fish and chips, likely brought by Sephardic immigrants and best eaten with several shakes of malt vinegar, and even tempura, a descendent by way of the pescado frito introduced to Japan by Portuguese traders and Jesuits. The names of those dishes are not direct descendants, but they still have their own etymological relationship.

The kafana is a kind of establishment that goes back to Ottoman times, a dimly lit third place where men would sit at wooden tables, drink rakı, and do things like plot or get away from their families or read poetry. The word is related not to gambling or music or sorrow or decay but to кафа, the word for “coffee.” It’s derived from the Turkish kahvehane, “coffeehouse,” which in turn comes from the Arabic قهوة (qahwa), the ancestor of most modern words for the thick, bitter drink that Ottoman kafana patrons would sip all day. Serbia was under Ottoman rule for 350 or so years; here is just one example of a type of language change that linguists call “borrowing.”

The lexicon at Kafana is both easy to grasp and expansive in its usage. Phyllo, a yard of it wrapped around a cheese-and-spinach pie, the top fluttery-flaky and near burnt. Red peppers made into a pasty sauce, pleasantly bitter, almost acrid, the oil leaving a tinge of bright orange-red, carrying their pigment into everything it touches. Serbian peppers are renowned, the paprika the finest. Another example of borrowed vocabulary: Chiles only left the Americas about 500 years ago.

At Kafana, you can taste the root-word foods, the dishes whole languages of food are built from. Šopska, for example—that tomato, cucumber, onion, briny-cheese salad you’ve had before, the salad everyone says is theirs. It’s in that Greek-Turkish-Cypriot-Arab-Persian salad language family, testament to the porousness of borders. A special kind of mixed grill, one that is mostly pork: chops, necks, sausages, meatballs, bacon wrapped around dates wrapped around liver. Ćevapi, mincemeat on skewers, grilled over fires in Balkan nations all—the name is derived from Turkish kebap, from Persian kabob, from Arabic.

Last time, we drank a bottle of Sauvignon Blanc, grapes brought from France, grown on Danube banks that were first planted by the Romans back when the place was called Illyricum. The back of the bottle read: “develops slowly, in layers.” And mashed potatoes, called pire krompir, borrowed from Austrian-German grundbirne (“ground pear”). After the Romans, of course, and after the Ottomans, there were the Austro-Hungarians.

And then there are the food-root words, the words for things so basic we have been eating them since before we spoke, since before food writers ever thought about the idea of a “cultural crossroads.” See jagnjeća kapama, leafy-green lamb stew. Jagnje (lamb) is from Proto-Indo-European—see agnus dei, see agnello e piselli. In čorbast pasulj, winter ham-hock bean soup, we see pasulj stemming from the same source as fasoolia, fagioli, and frijoles. In a historical linguistics class I was once shown a map overlaid with multicolored arrows, how words and syntax got pushed and pulled around the world by people making their little journeys, people who obviously needed to eat, who maybe killed each other, or married each other, but who surely all loved meat and beans.

Now, a smoked trout arrives, river trout, small—it is left whole and put down before us as it lies in state, skin opalescent and flayed for our convenience. Funereal goods in the form of parsley laurels and lemon wedges at its flanks. The pale flakes are dense and salty, toasty-sweet like caramelized birch. It might feel dangerous for its clouding deliciousness and for its implied warning—where there’s smoke, there’s fire. In reality, it’s just a cool brook and a country smokehouse.

The Serbian smoked trout is called dimljena pastrmka. Pastrmka. Is it related to pastrami, I wondered? That’s smoked too, after all, and vaguely Balkan in its lineage. I think I posited this aloud at the table, to nodding heads and sounds of mmm.

Googling later, I found that I’d been translating too forcefully: Pastrmka means “trout.” Thinking about food will only get you so far; to get the whole story, you have to eat it.

note: cash only

would order again: gibanica (cheese pie), zeljanica (spinach pie), dimljena pastrmka (smoked trout), pecena paprika (roasted red peppers), celer i cvekla (celery root and beet salad), mešano meso (mixed grill with ćevapi, sausages, smoked pork neck, pork chop, and prunes and chicken livers wrapped in bacon), a bottle of Bikicki S/O or any Serbian skin-contact wine